Nobel Prize winner in Literature (2022) and French feminist author Annie Ernaux hasn’t always supported the legalization of surrogacy. But, the evolution of her stance is a reflection of the intricate paths of feminism. Here is the English translation of our interview with the writer.

Interview Nicolas Scheffer & Morgan Crochet, English translation by Naïma Saidi

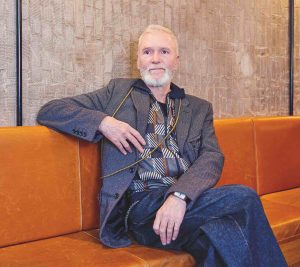

“I no longer do many interviews, I’ve stopped.” A year after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, Annie Ernaux has had her fair share of public exposure. And yet, when têtu· asked her to speak on a topic she admits to be “highly-flammable”, she accepted. “That’s precisely it, I haven’t been asked about surrogacy”, she confides bluntly. And while Annie Ernaux is well-versed on the matter, she’s not here to lecture anyone. If anything, as a left-wing writer whose position has changed with time, she merely wishes to share the way she sees things now. At 83 years old, this four-time grandmother is without a doubt our greatest witness of the evolution of both the political and intimate aspects of women’s status in France, from the 1940s to the revolutionary liberalization of abortion laws and contraception, which she addresses in her book L'Événement [The Happening], published in 2000. She says it herself: her voice is not worth more than any other, nor does it end the debate on surrogacy in any way. Before anything else, it’s the point of view of a woman, and undeniable feminist, and is worth listening to carefully.

Vincent Lacoste est en cover du têtu· de l'hiver🌟

– sortie ce mercredi 29 novembre – avec une interview exclusive d'Annie Ernaux mais aussi @kylieminogue, @zahodesagazan, @ocean_officiel, @MichaelLannan, John Waters, Ruben Alves, Christophe Mecca, et 30 millions d'alliés… pic.twitter.com/TMwo9p0iyW

— têtu· (@TETUmag) November 27, 2023

You are a feminist author whose work often explores the theme of freedom. How do you approach the subject of surrogate motherhood?

It’s an issue that relates to societal choices but also life choices, and the arguments on either side can be seen as valid. To be completely honest, in twenty years, my point of view has evolved: I was once against surrogacy, because of the dark realities and abuse that come with its commercial aspect, which directly impact financially-vulnerable women who turn to it, to survive. Human bodies, and women’s bodies in particular, are routinely trafficked, weakened by difficult working conditions, and unable to escape these relations of economy and domination.

What made you change your mind?

I witnessed the surrogacy of a gay couple in my inner circle. They went to Canada, where surrogacy is legal, and I followed them throughout the entire procedure. They showed me photos of the surrogate mother, who was middle class, and shared each step of it with me. I was able to see the process and understand that carrying someone else's child is a genuine choice made by surrogates, not just a financial one. I’ve met women who truly enjoy being pregnant and carrying a baby, but not necessarily raising a child. And now, this little Canadian-born girl, and her younger sister who was born the same way, are both growing up in a family just like any other.

Why does France struggle so much on the subject?

On this aspect, the concerns of French law are purely ethical. There’s this idea of divine motherhood, almost “Motherhood” with a capital “M,” with all the heavy implications that come with it: mothers carry all of the responsibility, sometimes even all of the guilt, and yet they are also seen as goddesses. I believe the link between child and maternal body does not need to be worshipped. Adopted children, for instance, aren’t unhappy children. But there’s a clear shift towards individual freedom and I think it’s just a matter of time. All in all, surrogacy will eventually gain ground.

Incidentally, the polls clearly show the French are largely in favor of legalizing surrogacy…

There’s been an evolution in our concepts of life and death, and the choice to die. At both ends of life, we’re questioning things we’ve never questioned before, things that relate to individual consciousness. Nowadays, there’s a much stronger individual awareness than twenty years ago. After a long struggle, women finally have access to A.R.T. (Assisted Reproductive Technology), but the struggle is constant ! The father figure is also evolving, slowly but structurally. Some fathers are far more invested in paternity and same-sex marriage helped reveal many men’s desire to be fathers. And there are also many women who do not wish to be mothers.

Are you ever afraid of the backlash you might face for your opinion?

Yes, undoubtedly and I’m also not a very good debater, but I simply want to express my point of view. From experience, I’m equally aware that most opinions and judgments are built on sensations and perceptions. But simply put, when you see both children born through surrogacy, and surrogate mothers, who are happy, it becomes quite obvious. In the same way that there are right-wingers who ultimately, have no issue with same-sex marriage. To quote René Char, by looking at it, they'll get used to it.

In your book L'Événement [The Happening], you mention a clandestine abortion. Do you believe legalized surrogacy could help avoid these clandestine practices?

As long as surrogacy is prohibited in France, couples will naturally continue to go abroad. And there are no ethical issues in places where surrogacy is regulated, like Canada. But in countries with no reproductive rights for surrogates, the process is much harsher. And these scenarios must be avoided at all costs.

Could there be such a thing as feminist surrogacy?

There already is, in the way that it reaffirms that women have a right to full bodily autonomy. That aligns with feminism and women carrying children for other women, who may be infertile, is sorority in a way. Historically, women have also been known to voluntarily give up a child to other women.

Do you believe bodily autonomy is an absolute right?

We live in a society and, as a result, there are necessarily rules of living together which must deal with this freedom. It’s a subject that relates both to philosophy and sociology, but also to individuals, who react conscientiously and physically.

Your book La femme gelée [A Frozen Woman] describes a difficult pregnancy, a very different experience than the Canadian example you mentioned before…

Indeed, but La femme gelée takes place over 50 years ago. My first pregnancy dates back to 1968, under the “old order” of women’s rights. Having a child then wasn’t easy, and for women intellectuals, it was actually unthinkable, because nothing was done to accommodate it. Then my views on pregnancy changed following the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s, when I understood that women could choose to have a child.

Where would you say motherhood starts?

Motherhood is what happens between a woman and a child, all through their lives, whatever the conception. It’s a relationship. Obviously when a child is born, you experience a shock, a very strong feeling, but motherhood didn’t just happen to me suddenly, I had to learn it.

The main argument that feminist critics raise is that surrogacy commodifies the female body. How do you address the issue of surrogate compensation?

Surrogacy free of charge is hardly imaginable, it’s never entirely free, and that’s also what helps prevents domination. Surrogacy is a donation but also a service provided. Giving a legal framework to that transaction helps avoid deviations. I think from the moment a country legalizes surrogacy, it also has to regulate the economic aspect.

Ten years ago, you told têtu· you were surprised by the support the LGBTQI+ community showed you. Do you understand why now?

Well I’m actually more surprised that it came as a surprise to me then. I once was invited to Le Père tranquille at Les Halles in Paris and was superbly welcomed by a crowd of men, it was epic. At the time, I was presenting my book Passion simple [Simple Passion] which turned out to be very popular with gay men.

À lire aussi : GPA pour toustes : il est temps !

Photo credit : Jules Faure